Is Upcycled Fashion a Passing Trend or the Future of Fashion?

Upcycled, sustainable fashion is a growing trend, thanks to designers like Zero Waste Daniel and Grant Blvd.

Updated July 31 2020, 5:29 p.m. ET

Walk into Zero Waste Daniel or Grant Blvd’s ateliers in New York City and Philadelphia, respectively, and you’ll see endless bins of fabric scraps. I don’t mean the trash bins filled with discarded fabric that you’d find at any other fashion studio, but rather storage bins that hold onto each and every piece of unused fabric that comes through their doors, where they await being creatively added into a piece of upcycled fashion in the future. This is in stark contrast to the policies of most major fashion brands, several of which have been the subjects of backlash for incinerating, trashing, or otherwise destroying leftover stock and fabric rather than donate, reuse, or even sell it at discounted prices.

In direct opposition to fast fashion and its wasteful tendencies, the sustainable fashion movement has grown in recent years — but there are two ends of the spectrum. On one end you have major fashion brands with shiny sustainability initiatives that lean more towards greenwashing than genuine advancement; on the other end, you have companies like Zero Waste Daniel, who transforms fabric scraps that would otherwise go to waste into “reroll” to make new, classic, gender-neutral garments, and Grant Blvd, who “remixes” thrifted pieces into new looks that play with the gender construct and address social justice.

If it’s possible to turn a profit while being legitimately sustainable, zero-waste, animal-free, ethical, and essentially checking off everything on a mindful consumer’s list, as these growing brands are proving, why does the fast fashion industry fall so far behind when it comes to sustainability? As consumer demand for mindful, low-impact garments continues to grow, fast fashion brands will eventually have to change their ways — but how will the trends that have grown out of a need for genuinely sustainable fashion impact the industry as a whole?

Is upcycled and remixed fashion just a passing trend, or is it the future of fashion?

Fast fashion is more wasteful than you think.

Fashion is responsible for 92 million tons of global waste every year — that’s about 4 percent of the world’s entire waste, according to a report by Pulse Of The Fashion Industry via Forbes. Most of that comes from leftover fabric unaccounted for by clothing patterns, which most brands simply toss. But one’s trash is another’s treasure — and there are a few designers who have turned that perspective into a business.

Zero Waste Daniel pioneered turning fabric scraps into fashion.

Daniel Silverstein modeling a Zero Waste Daniel shirt and pants, which are entirely made from leftover fabric.

While studying design at FIT, Daniel Silverstein found himself tossing endless fabric scraps into the trash — and it reminded him of the fabric scraps his mother bought him to practice sewing when he was a design-obsessed 5-year-old.

“Those metal bins that I was pulling scraps out of as a kid, looked awful similar to the ones I was throwing scraps into in school,” Silverstein tells Green Matters over the phone, adding that he saw the wasteful nature of making clothing as a “missed opportunity” before he even realized the economic or ecological impact of that waste.

“When I was a student, sustainability was a club you could join. It certainly wasn’t anything you could major or minor in,” he recalled. “It really didn’t surpass more than the organic cotton, natural dye conversation.”

In 2010, Silverstein founded his eponymous fashion line, which was created from zero-waste patterns — something that no one seemed to care about a decade ago.

“It was challenging to get people interested in that aspect of the designs. People mostly wanted to just talk about what they looked like,” he explains, adding that at the time, people were just not ready for the buzzword “zero waste.”

Zero Waste Daniel changed direction to shake up the industry.

After five years of designing under his own name, he was looking for a new approach that would make “more noise in the industry.” At the time, Stella McCartney was possibly the only mainstream designer talking about sustainability in the fashion industry, according to Silverstein, and he wanted to be the next designer to add to the conversation.

In March 2015, the designer made his first patchwork shirt out of a collection of small black fabric scraps. Silverstein shared his creation to Instagram — “I really wanted a new shirt, so I made one!” read the caption — and the post received a positive response. Soon after, he launched Zero Waste Daniel.

Many of Zero Waste Daniel’s designs today still incorporate “reroll,” his signature fabric composed entirely of fabric scraps; but at the same time, over the past five years, the brand has expanded in various directions, all while keeping sustainability and upcycling at the core.

Upcycling fabric has become a trend.

Silverstein applauds other designers using similar upcycling techniques — as long as they are legitimately sustainable. “I love that that trend has grown. And I love my relationship to that trend growing,” Silverstein says.

He’ll be keeping an eye on the fast fashion industry to see if they start taking a page out of book, or if they just start knocking off eco-conscious styles with a lack of genuine sustainability, ethics, or transparency behind the garments.

“We hear that sustainability is a trend, but sustainability means something so much deeper than what a style looks like,” he explains. “It actually means being able to maintain what we’re doing at a specific rate or level. And we’re actually seeing in this moment a shift in the rate at which stuff is being manufactured. To see this trend growing, it actually means that people are not just copying the style of it, but the manufacturing of it — then we’re making measurable change, and that’s very exciting to me.”

Grant Blvd is remixing fashion — and making people think.

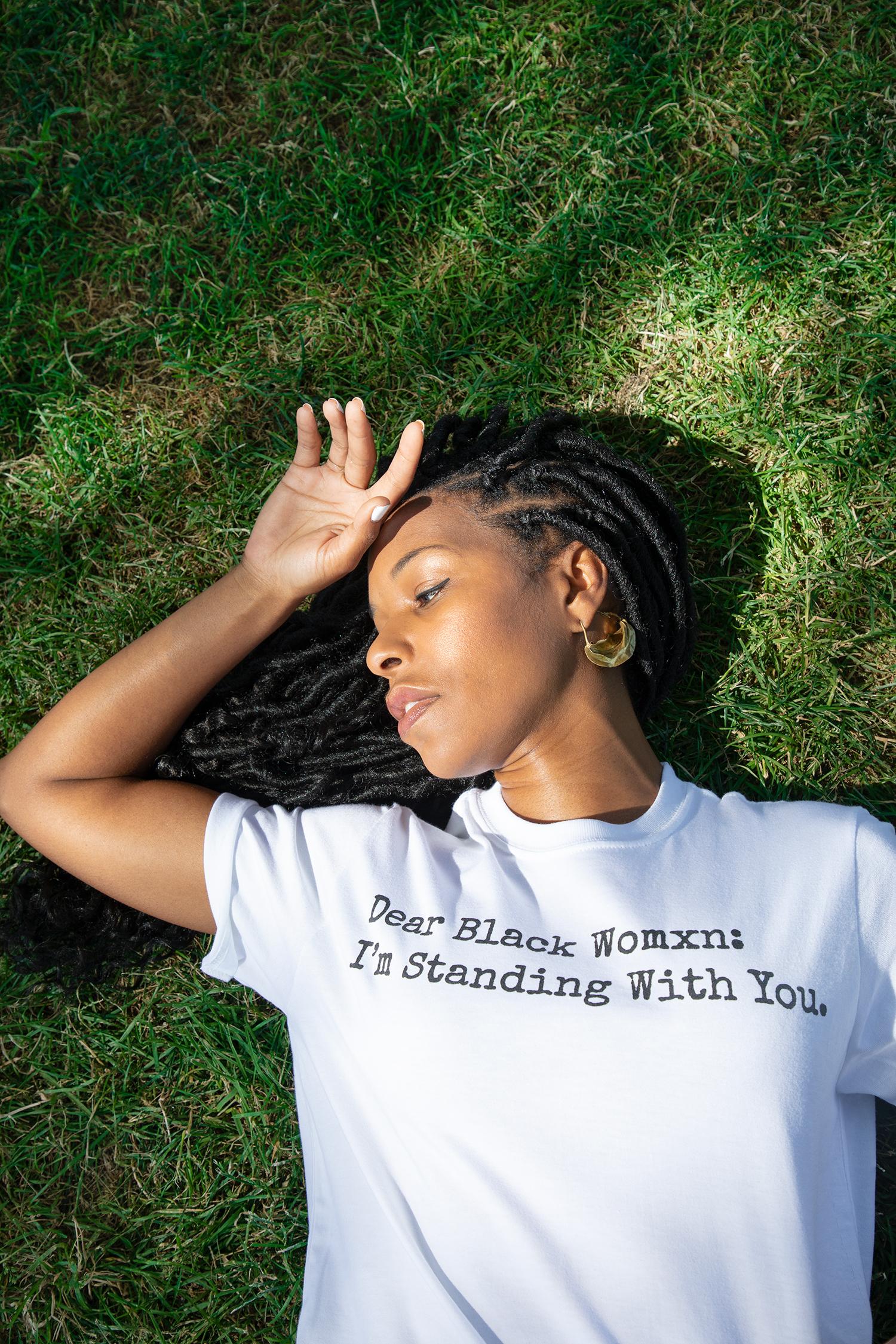

Kimberly McGlonn wearing a Grant Blvd T-shirt, made by screen printing text on a thrifted top.

Founded by Kimberly McGlonn, Ph.D., in 2017, Grant Blvd is a Black-owned, womxn-owned fashion brand that remixes secondhand garments into new pieces. The company’s goal is to create “fashion forward garments with a mindfulness toward the intersectionality of environmental and social justice.”

The team’s process begins with “a color theory, a story, a mood.” Then, they source garments from thrift stores that align with the vibe in mind. Then, Grant Blvd’s designers cut, sew, upcycle, and remix their finds along with the fabric scraps that they have been accumulating for 2.5 years to create their biannual collections.

Each piece Grant Blvd makes is one of a kind, whether that’s done by turning a men’s button down shirt into a feminine blouse, screen printing social justice-fueled sayings like “Sustainable AF” or “End Mass Incarceration” onto T-shirts, or restoring a pair of vintage pants with colorful fabric scraps.

Fast fashion needs to start thinking about waste and sustainability.

Sustainability guides Grant Blvd’s values, and McGlonn thinks that the fashion industry at large may eventually feel pressured to do the same.

“It’s quite possible that large companies will start thinking about waste management differently,” she tells Green Matters, noting that the ways COVID-19 has disrupted the supply chain may force some large brands to start thinking about things like waste — even if it’s just from an economic perspective.

However, McGlonn’s main concern in improving the sustainability of the fashion industry lies in its profit-motivated leadership. “If the same people who have been so committed to creating a profit from these massive problems continue to lead, then how can we expect any degree of real, meaningful, measurable change?” she wonders. “And I don’t think we can. The hope is that as they start to recalibrate their approach and their system that they’ll also rethink their leadership model.”

That said, consumer demand is shifting, and McGlonn believes companies are finally becoming aware of that. But she’s not going to wait for them to give her permission to follow their lead — she’s going to lead this movement.

“Why not just be the wave? I’m not going to wait for [major fashion corporations] to determine what’s right,” she says. “I’m going to keep telling our story, and keep explaining our process and approach and our pinpoints, and then just lead the way, versus a response to what fast fashion and luxury brands are doing. We’re gonna just respond to the need and make it playful and fun and sexy, all those things that I think are often missing a little bit in the sustainability conversation.”

Grant Blvd is not letting momentum die down.

Earlier in coronavirus quarantines, there was a massive wave of people supporting Black-owned and womxn-owned small businesses — and McGlonn feels that momentum has sadly died down. (But Grant Blvd just opened its first brick and mortar shop, in Philly, so hopefully that will reignite support for her company.)

“We have to stay the course [in] our commitment to small businesses, to Black-owned businesses, particularly in places like Philadelphia, where less than 2.5 percent of small businesses are owned by Black people,” McGlonn says. “We need a continued commitment to making the lifestyle choice of thoughtful consumption.”

The fashion industry will have to change eventually.

Making a personal commitment to only shopping for sustainable fashion is not a concession, but rather a way of living your values, creating more individuality and uniqueness in your wardrobe, and affecting demand in the fashion industry. As more people make the choice to put their money into independent, sustainable, ethical, or secondhand fashion brands rather than fast fashion, the fashion industry’s major players will eventually realize they have to change.