Earth Day May Be 50, But Its Message Is as Timeless As Ever

The history of Earth Day reminds us that the more things change, the more they stay the

Updated April 29 2020, 4:15 p.m. ET

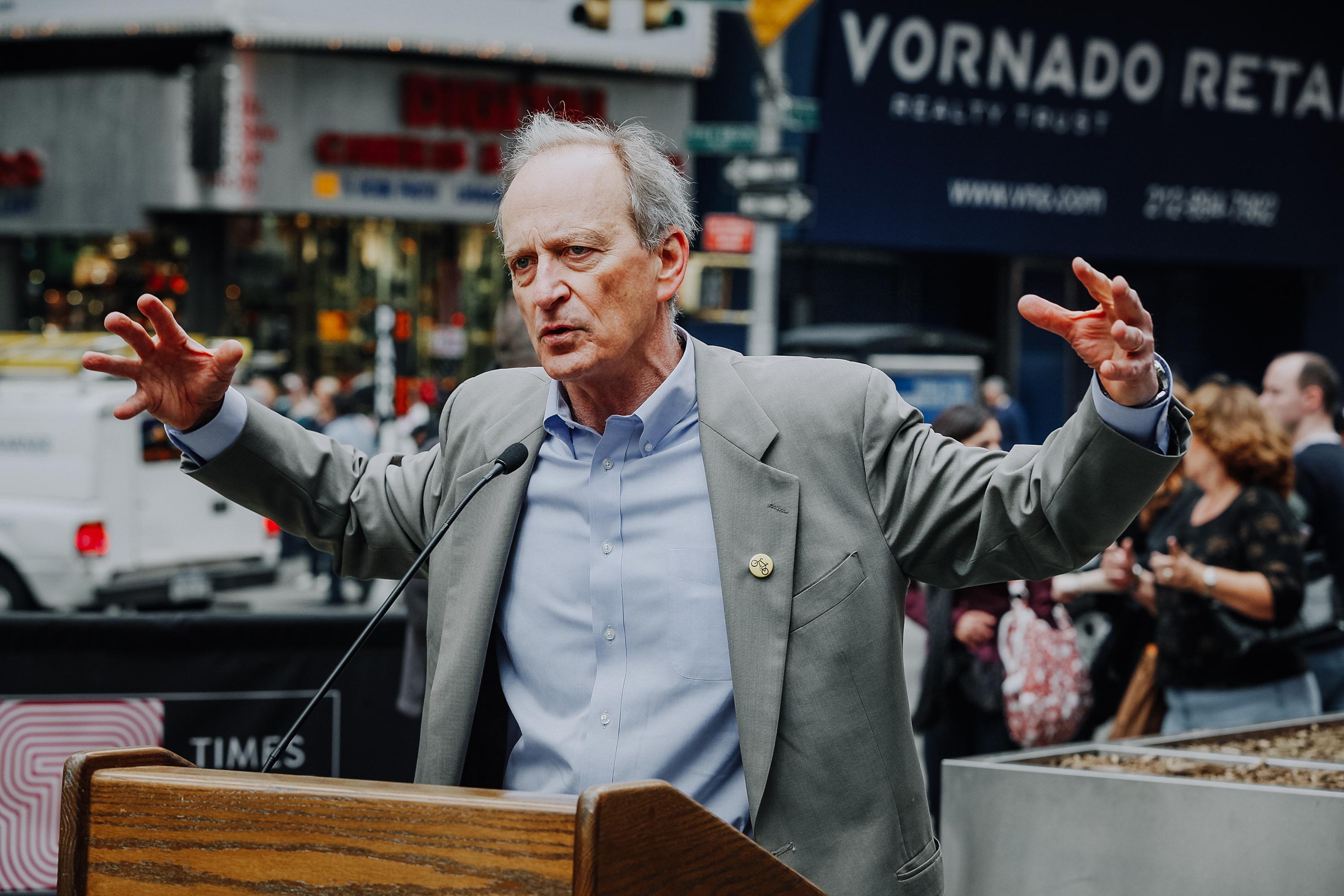

When Denis Hayes talks climate policy, people tend to listen; in the past month alone, the 75-year-old has penned an op-ed in The Seattle Times, been profiled in The New York Times, and was featured in The Washington Post. Today, you’d probably associate him more with the septuagenarian leaders that climate activists are rallying against than you would with the “youthful vitality” that he once said “forms the engine of [climate activism]” to Time.

But that’s because he first entered the spotlight 50 years ago; at age 25, he opted to drop out of Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government when he got the call from a grassroots organization back in his home state of Wisconsin that was about to change his life. (At age 25, he was also the oldest salaried member of a group of young people put together by Wisconsin’s former Gov. Gaylord Nelson, then Senator, to help bring awareness to the problems the environment — and therefore all the people living in it — faced.)

The cultural shift had people looking at everything differently — and the environment was no exception.

The 1960s saw revolution in just about every aspect of our culture. The decade began with the 1962 publishing of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, which exposed the country’s troubling, and heavy, use of pesticides and the problems it caused for the environment and all living things. The research proved the damage to the environment caused by humans — in this case, the mass spraying of pesticides such as DDT weakened ecosystems — but also showed how the problems in our environment ending up causing even more problems for humans and animals alike (in Silent Spring, Carson predicted the increased use of pesticides would result in certain pests developing resistance to pesticides, and the increase of invasive species could cause entire ecosystems to collapse further).

At the time (and still for so many of us), coming together and speaking out became the way of life; all over the country — especially on college campuses — young people, sick of seeing their friends and peers drafted, were protesting the Vietnam War; the publishing of Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique in 1963 kicked off second-wave feminism, and had once-homebound women marching for equality; the decade began with young, black activists peacefully protesting with sit-ins and taking freedom rides to fight back against segregated bus stations, and ended with the Stonewall Riots, in 1969, a violent, anti-LGBTQ attack often credited as acting like a catalyst for the gay liberation movement, and, ultimately, the first LGBTQ pride marches.

The climate was something that affected everyone.

For so many people, the counterculture and activism of the 1960s meant that you didn’t have to take whatever life dealt you — you could fight back against the problem; and with newfound understanding of the world around them, knowing what troubles plagued the environment, meant the threat was in our backyards.

And, unfortunately, the problem didn’t stop with pesticides. In early 1969, there was an oil spill in Santa Barbara, which was at the time the nation’s worst (but has since been passed by the 2010 Deepwater Horizon and 1989 Exxon Valdez spills, the No. 1 and No. 2 worst oil spills on U.S. soil, respectively). The spill had horrible consequences for marine life, and a big PR problem — one that was only made worse when, only a few months later in June, an oil slick in Cleveland’s Cuyahoga River caught fire.

The Santa Barbara Oil Spill killed at least 3500 sea birds — and brought environmental issues to the forefront of the American consciousness.

“A number of issues basically all came to a head by the late ‘60s, starting in 1962, with Rachel Carson publishing Silent Spring, about the dangers of pesticides. In 1969, an oil spill in the elite community of Santa Barbara, Calif. brought it home to people in a terribly visible way — they saw animals covered in goo, people trying to get it off, and you just watched them die on camera,” Hayes told Time last year. “Then we had the fire on the Cuyahoga River; the juxtaposition with water, which puts out fire, made a splash.”

But as the country started to expand, just as the interstate highways were being erected, even “people who didn’t self-identify as conservationists” took notice of air pollution, Hayes explained. Suddenly, it wasn’t just seabirds or dolphins covered in something so undesirable — it was you, your children, and everyone you loved. He added, “That’s when people who didn’t self-identify as conservationists were out there trying to protect their neighborhoods from horrible air pollution. The stuff coming out of tailpipes was all from leaded gasoline, poisoning their children. At the same time that people were trying to talk about organic produce and the impact of pesticides on the foods that people were eating, those pesticides were being sprayed onto the backs of farm workers … What we did was take all of those myriad strands, including wildlife protection issues, and wove them all together.”

The desire to make the planet a better place continued to bring people together.

In 1969, activist John McConnell took the stage of the UNESCO Conference and shared his idea to have a day to honor nature and the natural world. On Jan. 28, 1970, the one year anniversary of the Santa Barbara oil spill, locals celebrated Environmental Rights Day, which was organized and led by Marc McGinnes, who worked closely with Congressman Pete McCloskey to create the National Environmental Policy.

Scenes from the first Earth Day event in NYC.

Everything happening all over the country was noticed by one politician, former Wisconsin Gov. Gaylord Nelson — who was the Badger State’s Senator at the time. He noticed the planet was in danger, and inspired by the “teach-ins” led by the young advocates against the Vietnam War, he envisioned a large, grassroots demonstration that would not only give people a space to share environmental concerns, but also a platform to urge his fellow government leaders to take action. After announcing his plans for an event he dubbed “Earth Day” at a conference in late 1969, he invited everyone in the country to get involved. And people seemed to have found in Earth Day an opportunity that they had been longing for.

“The wire services carried the story from coast-to-coast. The response was electric. It took off like gangbusters,” Sen. Nelson, who passed away in 2005, previously recalled. “Telegrams, letters, and telephone inquiries poured in from all across the country. The American people finally had a forum to express its concern about what was happening to the land, rivers, lakes, and air — and they did so with spectacular exuberance.”

It was shortly thereafter that April 22 was selected for the first Earth Day; according to Hayes, who was named the cause's national coordinator, the date was picked because Gov. Nelson wanted a day late in April, between Spring Break and finals, in hopes of warm weather so most of the country — especially college-aged students — would be able to enjoy the outdoors as part of the demonstration. He then picked a Wednesday in hopes people wouldn’t be traveling on any weekend trips. Once the date was established, the movement and event were given a name — Earth Day — first coined by Julian Koenig, the ad man behind Volkswagen’s famous “Think Small” campaign.

Participants — including many young people, not unlike today — took to the streets in NYC on the first Earth Day.

Hayes was put in charge of finding organizers who had experience with the activism that defined the decade before but, because of the war at the time, Hayes said college students weren't the active demographic they'd hoped for at first. But there was one group that stood out to Hayes when he was reading the mail coming into the Governor’s office: young women.

“I looked back at the mail to the Senator’s office, and it was overwhelmingly from relatively young women, mostly college educated, with one or two kids in a single-wage-earner family, with time on their hands, who had gotten frustrated by not being involved in the social tumult of the era and who were deeply affected by the environmental threats to their children,” he said. “They formed a real nexus we organized around. Once the thing got visibility, and it became clear this was a vehicle for change, then the students climbed on board afterwards.”

The value of Earth Day was always understanding how every person had an impact — but when they came together, the power was undeniable.

The first Earth Day, held in 1970, was celebrated in major cities in the United States (New York City’s Mayor John Lindsay even shut down Fifth Avenue), more than 2,000 college campuses, and around 10,000 primary and secondary schools. On that first spring day at the turn of the decade, 20 million Americans — an impressive 10 percent of the entire U.S. population — got outside and made their voices heard in the name of climate activism.

The power was, undeniably, in numbers — but what was perhaps the most impressive is the way the groups mobilized themselves. Gov. Nelson previously explained that the success came because of its grassroots nature — this was for the people, by the people (not unlike the climate strikes of today). “Earth Day worked because of the spontaneous response to organize 20 million demonstrators and the thousands of schools and local communities that participated,” he said. “That was the remarkable thing about Earth Day: It organized itself.”

In 1990, Earth Day went global — but still had more support than ever home in the States.

Earth Day was always political — without ever being partisan.

Earth Day wasn’t just about giving concerned Americans a platform to lament about the growing environmental concerns; it was also motivated by the desire to see political change. As Earth Day declares on its website: “Earth Day inspired 20 million Americans...to take the streets, parks, and auditoriums to demonstrate against the impacts of 150 years of industrial development which had left a growing legacy of serious human health impacts… Groups that had been fighting individually against oil spills, polluting factories and power plants, raw sewage, toxic dumps, pesticides, freeways, the loss of wilderness, and the extinction of wildlife united on Earth Day against these shared common values. Earth Day 1970 achieved a rare political alignment, enlisting support from Republicans and Democrats, rich and poor, urban dwellers and farmers, business and labor leaders.”

By the end of the year, it was clear that these voices were heard: 1970 saw the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency and the passage of the Clean Air Act. In 1971, President Nixon sanctioned Earth Day as a holiday, which was followed by the passing of the Clean Water Act in 1972 and the Endangered Species Act the next year.

Denis Hayes speaks to a crowd to introduce the “Green Generation” campaign, launched on Earth Day 2009.

And in the decades that followed, the event has only grown larger and larger. In 1990, Earth Day went global, and started being celebrated all over the world. It was on April 22, 2016 — a date once selected mostly because it was smack in the middle of Spring Break and final exams — that more than 120 countries signed the Paris Agreement. The celebration has grown to such extreme sizes that today it’s considered the largest secular observation in the world.

Now, the founders of Earth Day are handing off the torch — even if this year’s observation may look a little different.

Greta Thunberg, arguably the leading climate activist of today, using the same energy and passion that fueled the first Earth Day to get today’s young people fired up about climate justice.

Though the celebration has grown and grown — and though, this year, Earth Day may look a little different as we all celebrate at a safe distance from one another — the message, and the method remain the same: It’s a grassroots movement inspired by making the world a better place. And while that isn’t inherently political, the movement has always been inspired by political action — fueled by today’s young leaders — to make tomorrow a better day.

In an op-ed for The Seattle Times, Hayes, who runs a foundation that provides grants to climate-minded organizations including many led by younger generations, made a proposal: In addition to whatever you do today, remember to also celebrate Earth Day on Nov. 3 — Election Day — and vote like the future depends on it. (In case you had any doubts about his track record, he shared an anecdote about how he and his Earth Day compatriots spent the summer of 1970 identifying 12 politicians with bad climate records, and low voting margins and labeled them the “Dirty Dozen”; the activism led to seven of the 12 being voted out, and the passage of countless environmental bills.)

“This April 22, we want everyone to stay in the safety of their homes,” Hayes wrote.

“But understand that the real challenge lies in the next six months. The 2020 U.S. election will be the most important of your lifetime… On Nov. 3, don’t vote for your pocketbook, or your political tribe, or your cultural biases. This Nov. 3, vote for the Earth.”

This article is part of Green Matters’ 2020 Earth Day campaign, #HomeSweetEarth, which aims to remind readers that the one thing we all have in common during this hectic time is our home: our shared home, planet Earth. We hope our stories this week will inspire you to connect with and honor the Earth during the pandemic — and beyond.