How Google Is Working To Curb Illegal Fishing

The transfer of fishing goods from one boat to another has seen a steady pace of illegal activity. Since many organizations that oversee this are lightly restricting it, Google and others are working to provide a large-scale monitoring system.

Updated May 24 2019, 7:44 a.m. ET

Is that fish you’re eating coming from an illegal transaction in the high seas? With the United States importing around 90 percent of the seafood we eat, there’s a good chance of it happening. Illegal transshipment is responsible for over $23 billion in economic loss. It’s been hard to monitor in the past, but new technology could aid in stopping the process.

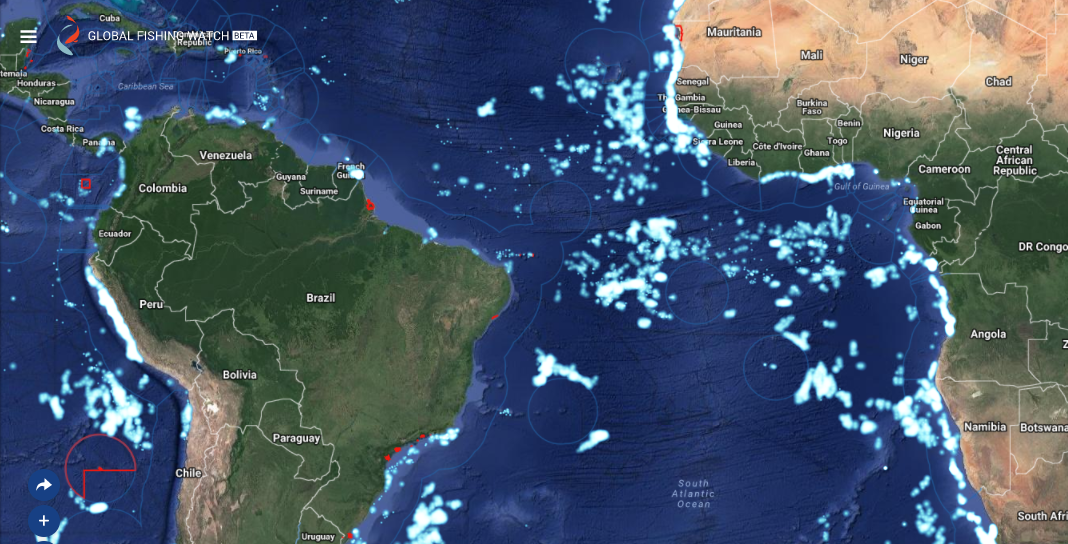

Thanks to a collaboration by Google, Oceana, and SkyTruth, anyone has the power to view where ships are located. This works in part because many boats need to have an identification system to avoid crashing into each other. Then, GPS systems are able to track the activity of these vessels, suggesting that with closer monitoring and more accountability, less illegal trade will happen.

Transshipment itself isn’t illegal. It happens when a fishing boat transfers its supply over to a reefer and eliminates the process of docking the boat on land. Since catching fish is both competitive and lengthy, these vessels would rather spend more time out in the waters than having to find a place to unload their cargo.

Problems arise, however, when some of this fishing is manipulated. There are laws that try to prevent people from using equipment that could give them an unfair advantage or allow them to fish where they shouldn’t be. Not only could this harm habitat for the fish, but it strongly affects the supply chain and the seafood economy. Without proper monitoring, billions of dollars have been lost due to illegal activity.

It’s also been linked to more crimes, such as slavery and human trafficking. A study from New York University back in April looked into 17 regulation facilities, called Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMO). They discovered only one of them issued a full ban on the practice while five handed out partial bans.

Ultimately, a conclusion reached by the authors was to ban transshipping entirely: "A total ban on transshipment at-sea on the high seas would support the ability of oversight and enforcement agencies to detect and prevent illegal fishing and also likely reduce human trafficking and forced labor on the high seas.”

Organizations have been working on projects to help monitor the waters and halt this practice. Global Fishing Watch is among the biggest and most convenient.

Results have been very promising for the technology as it recorded over 91,000 possible transshipments between 2012 and 2016. SkyTruth, a company that uses satellite imagery and remote sensing data to identify environmental issues, received help from Google’s technology in the process. Oceana chipped in with the Automatic Identification System (AIS).

John Amos, founder of SkyTruth, noted that it was stunning to see the results of the system, saying, "As we worked with the data, we realized we could tell in many cases what a vessel was up to based on way the vessels were moving on the water. It didn’t really hit home until we put their AIS data broadcast on a map."

The only caveat is these AIS systems aren’t always reliable. They can be turned off, but that would send red flags indicating they are participating in illegal activity. That would end up with an investigation. A bigger issue is the signal can malfunction or it could be turned off as a tactic to avoid competition finding hotspots.

Should transshipment be banned altogether? It’s up for debate, but it definitely needs to be regulated more than it is. As technology with the Global Fishing Watch advances, there should be even better results on illegal activity being thwarted.