A Timeline of the Environmental Justice Movement, According to Dr. Robert Bullard (Exclusive)

We're taking you from the '70s to the '90s, highlighting just how vital Black voices were to the birth of environmental justice.

Published Feb. 28 2024, 4:45 p.m. ET

Reverend Joseph Lowery and supporters protest the Warren County PCB landfill in 1982.

With the climate crisis worsening, environmental justice is more important now than ever before — and it's vital to honor the ways that the environmental justice movement is rooted in Black history.

“Black Americans played an outsize role in building the environmental justice movement," Dr. Robert D. Bullard exclusively tells Green Matters via email.

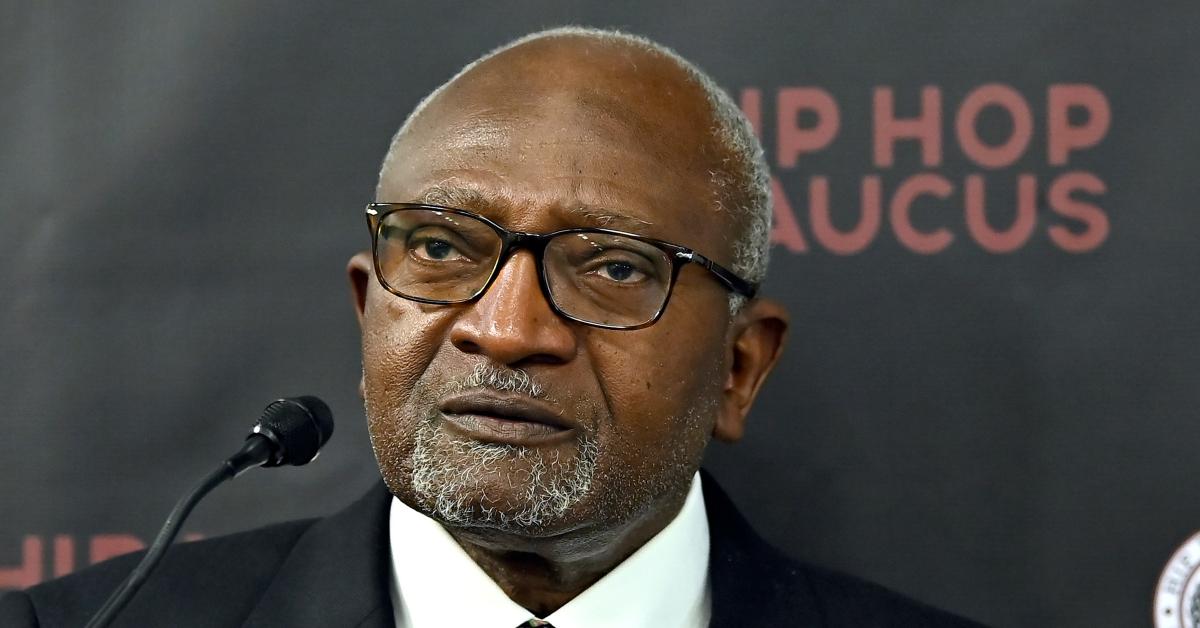

Dr. Bullard, a renowned author, professor, and activist, is often regarded as the "father of environmental justice" for all of his work in building the EJ movement. He has written 18 books on topics related to environmental justice, and he is the co-founder of the HBCU Climate Change Consortium and the HBCU-CBO Gulf Coast Equity Consortium. Later on in the story, you'll hear more about how instrumental HBCUs (historically black colleges and universities) have been in the climate justice movement.

Keep reading for our timeline of the EJ movement, from the 1960s up until the present day, along with some exclusive commentary from the legendary Dr. Bullard.

Dr. Robert D. Bullard speaks at the Hip Hop Caucus inaugural A. Donald McEachin Environmental Justice Award reception on April 20, 2023 in Washington, D.C.

The environmental justice movement's history takes us back to the 1960s.

Dr. Bullard once wrote that "whether by conscious design or institutional neglect, communities of color in urban ghettos, in rural 'poverty pockets', or on economically impoverished Native American reservations face some of the worst environmental devastation in the nation." These disparities led to the birth of a crusade.

The 1968 Memphis Sanitation Strike saw 1,300 Black sanitation workers call for fair pay and better working conditions after two garbage collectors were brutally killed by a malfunctioning work truck, as per History.

With a humanizing slogan, "I am a man," the strike even pulled Martin Luther King Jr. to the Tennessee city. The civil rights leader actively supported the strike until his assassination on April 4, 1968.

The U.S. EPA describes the historic strike as "the first time African Americans mobilized a national, broad-based group to oppose environmental injustices."

The EJ movement evolved when the first U.S. lawsuit opposing environmental racism via the Civil Rights Act was filed in the 1970s.

The landmark 1979 Bean v. Southwestern Waste Management Corp. lawsuit was a turning point in the EJ movement.

The suit came about in response to a private landfill site that was being planned just 1,500 feet from a school in a largely Black suburban community. When attorney Linda McKeever Bullard — who happens to be married to Dr. Bullard — heard about this, she sued Texas, Houston, and Harris County for racism under the Civil Rights Act, as per the AAAS.

On a mission to provide definitive data to support the plaintiffs, Dr. Bullard and his sociology research methods students gathered data and did intensive research. They found that 82 percent of Houston’s waste was discarded in Black neighborhoods from the 1920s through 1978.

Ultimately, the group lost the lawsuit, but Bullard told the AAAS that “we won the war,” as a law was later passed essentially shutting down the private landfill, and forbidding landfills from being constructed within 2 miles of a school.

Environmental justice events of the 1980s saw a correlation between race and hazardous waste site placement.

The Warren County, N.C., protest of 1982, which peacefully disputed a PCB landfill that was to be placed in a predominantly Black community, too, enlivened the movement. This is one of several events that fueled studies dedicated to proving the relationship between race and discriminatory waste sites, including Dr. Bullard's 1983 study, Solid Waste Sites and the Houston Black Community.

Dr. Bullard later penned his formative text on environmental racism just as the 1980s came to a close: 1990's Dumping in Dixie. Publishers initially pushed back, asserting that the environment doesn't discriminate. Of course, this is an ignorant simplification of what we now understand to be a complex issue.

The HBCU environmental justice centers of the 1990s helped further research and usher in fresh voices.

If it weren't for the HBCU environmental justice centers introduced in the '90s, perhaps the movement wouldn't be where it is today: An equality-focused cause that aims to reform modern issues like drinking water violations, disproportionate air pollution, and climate gentrification.

Dr. Bullard tells us these centers — including the Robert D. Bullard Center for Environmental and Climate Justice — "provided much of the foundational education and training, research, policy, and community engagement framework that guides us today." He relays that 15 of his books were written during his days as a faculty member at an HBCU.

"Our 'Communiversity' model laid the foundation for what is now referred as community-based participatory research," he continues. "We were doing CBPR before it had a name."

While CBPR can be traced back to social scientist Kurt Lewin in the 1940s, it was Dr. Beverly Wright of the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice who developed the Communiversity Model, which prepares "residents of communities to have a voice on critical issues, which begins with listening to community concerns first and then providing research, education, and training."

In the 21st century, the battle for environmental justice remains as important as ever.

The fight to pass the A. Donald McEachin Environmental Justice for All Act and keep Joe Biden's Justice40 Initiative fair are just some environmental justice battles of today. As this movement grows and evolves with our ever-changing planet and sociopolitical climate, it's essential that we honor the prominent Black leaders that helped to build it.